1.3 Using R

The following examples and exercises will give you a first look at what R does and how it works.

R is a “command-line” program, which just means commands can be entered interactively line-by-line at the prompt. As with all programming languages, everything has to be entered just right. R is case-sensitive, so mean(variableName) is not the same as mean(VariableName) or Mean(variableName). And the syntax uses quotes and other delimiters in very specific required ways. So it can take a bit of getting used to.

There are several ways of entering commands:

Type them out carefully into the “Console” (the lower-left window in Rstudio) and hit

Enter. This is best if you just want to try something quickly, but not so good for creating a set of commands that you can run again (a key feature of “reproducible research”).Write and edit lines in the script editor (upper-left window in Rstudio), and pass the code into the console by placing the cursor on the line (or select a group of lines) you want to run and

- hit

Ctrl-Enter(Cmd-Enteron Mac) - click the

Runbutton - or click the

Sourcebutton to execute all of the code in the script window.

- hit

For the most part, we will be typing single commands into the Console window. But for real data analyses (like the lab assignments), it is smarter to write all of your coding in a script window, and then save it as a text document (with a .R extension), which you can edit, extend, revisit, update and re-run at any point later.

1.3.1 R as a Calculator

R can do everything a calculator can do (and more). Addition +, subtraction -, multiplication *, division /, raising to a power ^, and many others.

1 + 2## [1] 33 * 4## [1] 122 ^ 8## [1] 2562 * (3 + 4) ^ 3## [1] 686and so on.

1.3.2 Assigning Variables

R can store numbers (and many other things) in placeholders called variables.

The assignment operator is <- (preferred) or =. It’s supposed to look like an arrow pointing left. We assign the value 5 to the variable X.

X <- 5Notice that using the assignment operator sets the value of X but doesn’t print any output. To see what value X contains, you need to type:

X## [1] 5Notice also that X now appears in the upper-right panel of Rstudio, letting you know that there is now an object in memory called X.

Now you can use X as if it were a number:

X * 2## [1] 10X ^ X## [1] 3125Note that you can name a variable anything, as long as it starts with a character.

Fred <- 5

Nancy <- Fred * 2

Fred + Nancy## [1] 151.3.3 Rounding

The round() function is useful for rounding answers numbers to a specific number of decimal places.

x <- sqrt(0.5)

x## [1] 0.7071068round(x, 2)## [1] 0.71round(x, 3)## [1] 0.7071.3.4 Vectors

Another simple object in R is called a vector, which is a collection of numbers. The function c() (which stands for “concatenate”) is useful for creating vectors:

c(3, 8, 5)## [1] 3 8 5We can also easily create sequences of numbers:

4:10## [1] 4 5 6 7 8 9 10Variables can contain vectors:

X <- c(3, 8, 5, 4, 9)We can access a particular element in a vector with [].

X[3]## [1] 5Now, let’s do some arithmetic with this vector:

X + 1## [1] 4 9 6 5 10X * 2## [1] 6 16 10 8 18X ^ 2## [1] 9 64 25 16 81Note that in all of these cases, the arithmetic operations are performed on a term-by-term basis.

You can also make a vector of text called character strings:

Names <- c("Alice", "Boris", "Chaozhi", "Diego", "Eliza")

Names## [1] "Alice" "Boris" "Chaozhi" "Diego" "Eliza"Now that we have some data, we can study them with simple functions:

sum(X)## [1] 29length(X)## [1] 5mean(X)## [1] 5.8Note that if you try to do something mathematical with characters, you get an error.

sum(Names)## Error in sum(Names): invalid 'type' (character) of argument1.3.5 Plotting

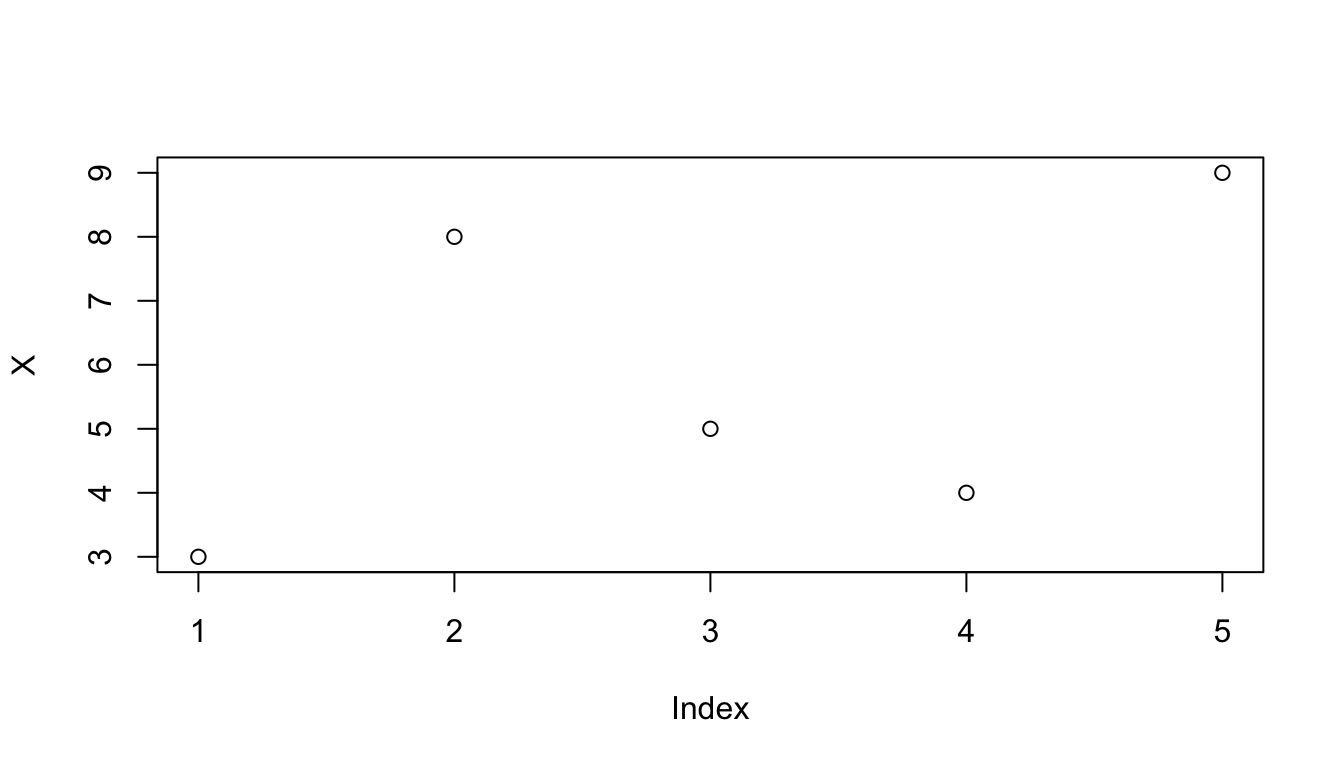

It is easy (but not very interesting) to plot the Data:

plot(X)

Notice that the figure appears in the lower right panel of the RStudio screen. Try using the “Zoom” command in the Plot tab command bar.

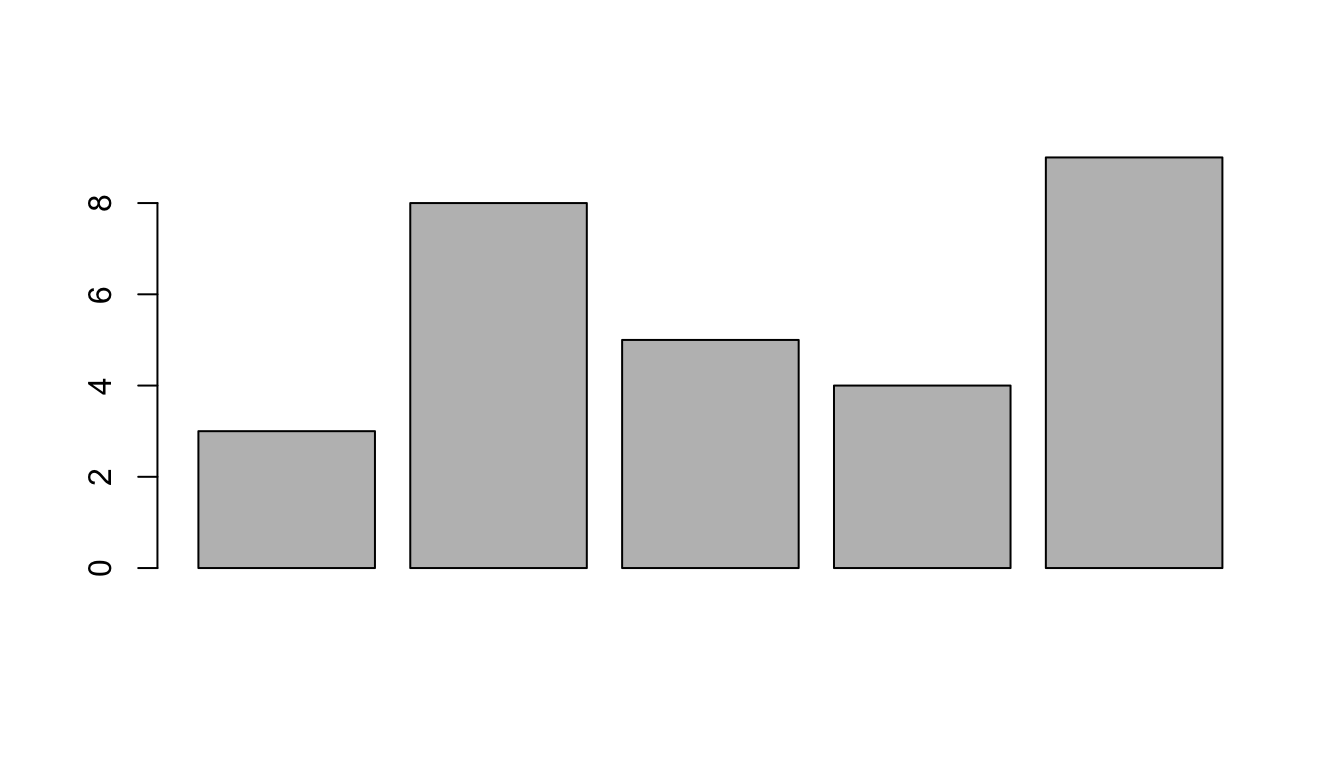

A “barplot” might be a little nicer:

barplot(X)

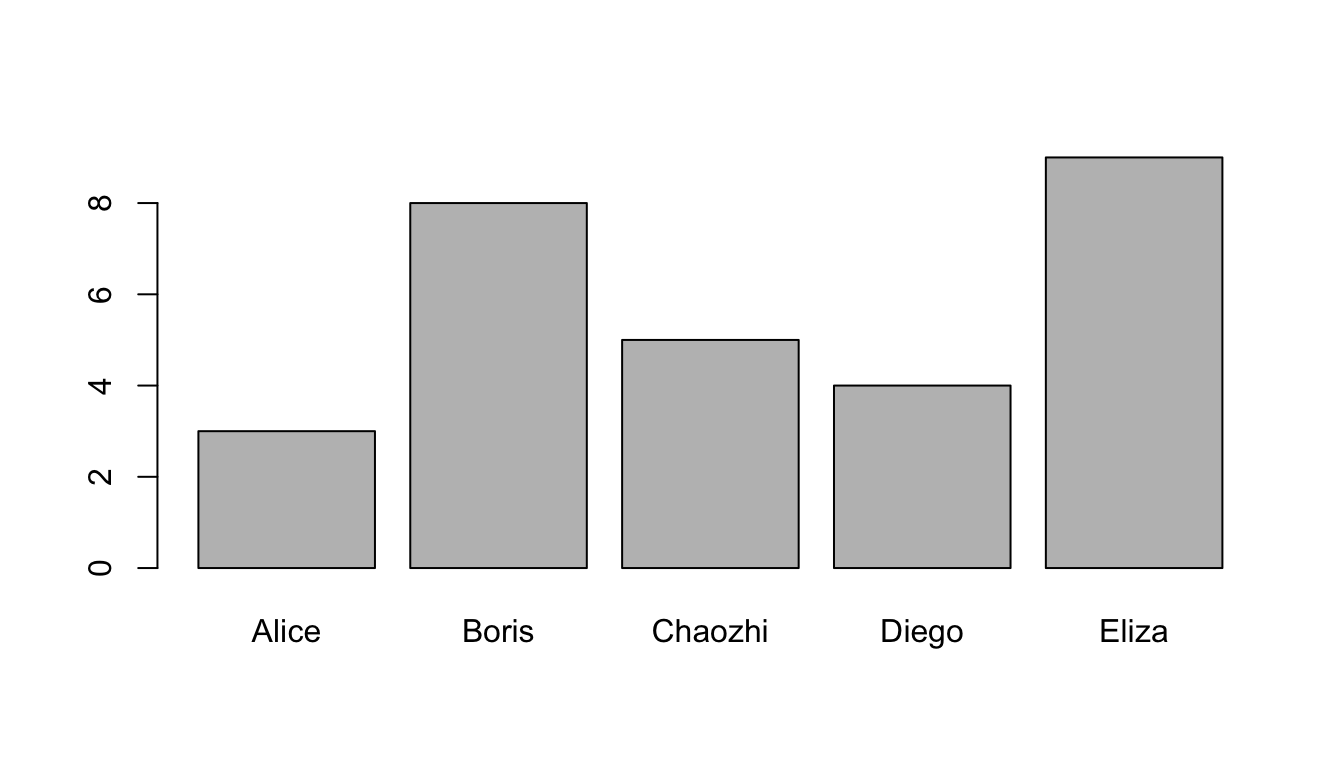

And we can give labels to the barplot by adding a names argument (note, that “argument” refers to any information that you give to a function).

barplot(X, names = Names)

Note that you can export the image using the Export button in the Plot command bar.

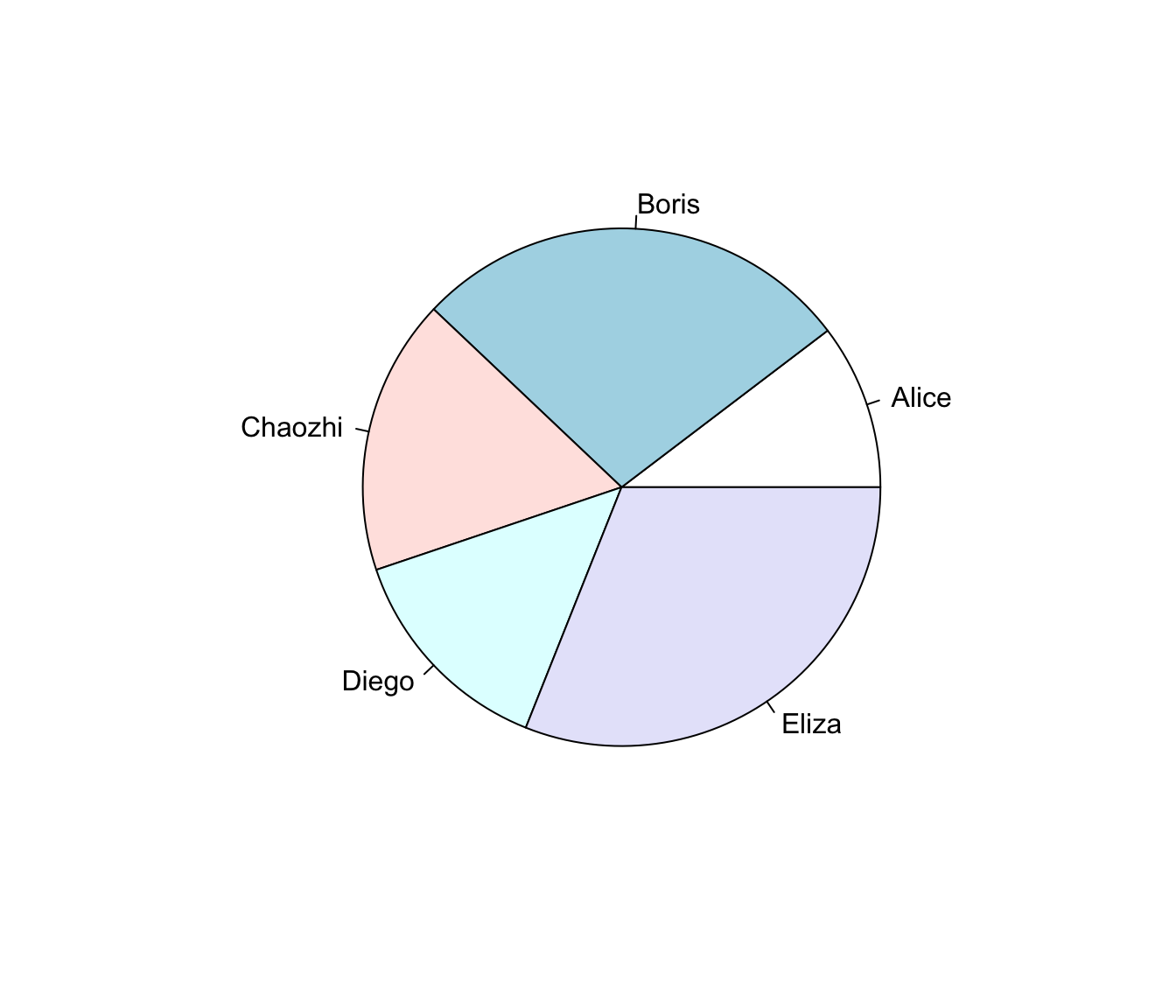

Here’s a pie chart:

pie(X, labels = Names)

Note that in barplot() the label argument is names, but in pie() the labeling is labels. Why, and how can we know? We check the help files (via ? or help()) or search online.

1.3.6 Exercises

- Make a vector called

Datathat contains, in order, the number of students sitting in your row, the number of people living in your house/apartment/dorm suite, the number of pets you have ever had, your age, and your shoesize. Make another vector calledNames, which contains short names for each of these numbers.

Example code:

Data <- c(1,2,8,36,9)

Names <- c("Students", "Roomies", "Pets", "Age", "Shoesize")Create an object called

Nwhich is the length of yourData, and use that object with thesum()function to calculate the arithmetic mean of your data. Try applying themean()function toData. Does it agree with your calculation above?The International Rhino Federation estimates that there 17,800 rhinoceroses (Rhinocerotidae spp.) living in the wild in Africa and Asia. Make a barplot and pie chart of these data.

Example code:

Species <- c("Black", "White", "Sumatran", "Javan", "Indian")

Population <- c(3610, 11330, 300, 60, 2500)

Rhino <- data.frame(Species, Population)| Species | Population | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Black | 3610 |

| 2 | White | 11330 |

| 3 | Sumatran | 300 |

| 4 | Javan | 60 |

| 5 | Indian | 2500 |